\\ lifting Isidro //

Dear Friends,

Last night I was driving my mother home from her choir practice around 10pm when I saw the glint of a wheelchair’s handles where I didn’t expect them. Someone sat in the dark in a folding wheelchair, parked on the sidewalk across from the hospital on Napolean Avenue near Claiborne. I felt in my chest that they needed help. My mind elevated into that calm, smooth, curious gear where nothing else exists but the present moment. I asked my mother if she would mind if we circled the block and I stopped to see if this person was stuck. She did not mind, she said — of course we should do that.

I got out of the car and walked toward the man in the dark, smiled, asked him if he was alright. He smiled back but didn’t say anything. He had a broad, open face, bright eyes and silver hair to his shoulders. I thought perhaps he was Deaf, but then asked if he spoke Spanish and he said yes, yes. Luckily I know enough Spanish to communicate like a fifth-grader, so we could converse. “Do you need help?” I asked. He nodded, “Yes, every kind,” with humor in his eyes.

When I got up close, I realized that one wheel was stuck in a round hole in the sidewalk about six inches deep and thirty inches wide, tilting him in such a way that he would not have been able to get out by his own strength. I felt joy that the problem could, possibly, be easily solved. In a few minutes, I wrestled his chair out of the hole without tipping him over. My mother came out of the car to help. At 83, with long silver braids, she is quite strong and scrappy.

The man blessed us in Spanish and held out his arm with a hospital bracelet. Isidro Martinez, age 66, released from Oschner Baptist hospital the morning of the day before. I told him my name and my mother's name. We shook hands. Mucho gusto. Encantado. He motioned to the bag on the back of the handle. I got it for him and he pulled out paperwork--his hospital discharge papers. I read them. I realized a catheter snaked from under his hospital garments to a clear plastic box of dark orange urine hanging from the wheelchair’s arm. “Have you been here since yesterday?” I asked. “Yes,” he said, “I’ve been here hungry and stuck.”

I turned to my mother — “He’s been stuck in the hole since yesterday!” Isidro was angled in his chair and sliding down, so I asked, “Can I lift you up back in the chair?” He said yes, so I went behind the chair and put my arms under his armpits and lifted him, expecting him to sit up straighter, but his feet, in hospital socks, got caught in the footrests. It was hard to lift him just a few inches up with all my strength. I came around to untangle his feet and he said, “The legs are no good.” I realized that he was paralyzed from the waist down.

“O, friend,” I said, “I’m sorry you’ve been here hungry and stuck! Where are you trying to go?” He said “219 Loyola, 219 Loyola,” wrapping his tongue around the English numbers. He repeated it a few more times in singsong like a nursery rhyme, the magic words that must help him get where he needs to be.

I turned to my mother, a question in my eyes. “That’s the main library,” she said. “At Tulane and Loyola Avenue. Not close.” I pulled out my phone to get directions. The Main Library was about four miles from our location. Oof.

There was no way Isidro could wheel himself four miles by hand over the cracked concrete, live oak roots, busy streets, highway intersections, puddles and antebellum sidewalks with no curb cuts. I looked at my mother and she shook her head slightly. We could not lift him into her car. And there was the issue of the full catheter box. Seeing she was tired and cold, I said, “Go back in the car to warm up!” She asked, “You’re okay?” I said, “Yes, of course.” I felt happy as I always do when given an assignment.

I asked Isidro, “You have friends there? At the library? You have a camp there?”

“Yes,” he said, “I have friends, my tent. I stay there. Lots of people camp there, many Black people with good hearts. They help me”.

“They help you get food and water and use the bathroom?” I asked. “Yes, they do,” he said. “Good hearts.” We talked more and I learned he was from Guatemala, had not talked to his family there in two years since he had a stroke. I thought about the situation. Isidro, 66, unhoused, recently hospitalized, paralyzed, trusting, hungry, thirsty, Spanish-speaking-only, marooned on a sidewalk. I walked to the car to brainstorm with my mother. How were we going to get him where he needed to go? It was possible, of course—we just needed to find the way.

A large van paused at the stoplight with Bridge House written in script on the side—a homeless shelter. The van was big enough to possibly have a wheelchair lift. I ran over to the van and the driver rolled down the window. “Do you have space at the shelter for this man they let out of the hospital? Or can you help us get him to the library?” The driver shook her head. “I’m sorry, there’s a long, long waiting list, my baby. I can’t stop.”

“Okay, no problem, thank you, honey,” I said, and she drove on. (This is how people talk to each other in New Orleans. It is good for my soul.)

The moon was very bright through the live oak trees and the shaking leaves made a shimmery sound like pennies. Isidro said he was cold. I dug in his dirty tote bag for a little fleece blanket to tuck around his legs. I found a smushed hospital peanut butter and jelly sandwich in a Ziploc bag. He ate it ravenously. Since his wheelchair had been stuck in the hole in the sidewalk since yesterday, he must be thirsty. I went to the car. "Mom, can I have your soda water?" She handed me the half-liter of Club Soda through the window.

Isidro took a sip. “Qué rico. ¿Esto es agua?"

"Agua con gas," I said, "agua mineral." He drank the bottle down.

The hero of this story is a man named Curry, but he wasn't there yet.

How were we going to get Isidro to his camp? The possible options: bus, car, taxi, Lyft, unicorn? I called my brother Edward and he answered on the first ring. "Would you please help me look up RTA bus times? I need to know what bus will run from Oschner Hospital on Napolean to the downtown library right now. The hospital left a paralyzed unhoused man out on the street and he wants to go to the library." "On it," he said. "There's a bus from Claiborne and Napolean to the main library leaving at 12:30 a.m. But it's only 11 now."

The intersection where the bus would pick up is an intersection where various substances and services that make people feel temporarily happy are sold. If I'd been alone, I would have pushed him the four blocks there and gotten on the bus. But tonight was not that night. I thanked my brother and hung up.

Isidro was looking at the moon, humming. I went back to the car. "Can we call a taxi for him? How much money do you have?" my mom asked.

"I have a twenty," I said. "Maybe they will take a credit card in advance."

"Oh! I have my secret stash!" she trilled. She lifted her armrest console. A piece of black construction paper folded into a small rectangle, stapled shut, was Velcroed to the underside of the armrest. "I keep a hundred-dollar bill in here. It's never been stolen no matter how many times they steal everything else," she said, pulling it off.

"But that's your money for when you need it, Mom. I don't want to take your emergency money."

"I keep it for a situation just like this!" she said. "A situation when I need it. Don't deny me the pleasure."

"Okay," I said. I looked up United Cab, gave our coordinates, and the dispatcher said a wheelchair-equipped taxi was on the way. High-five, Mom!

I walked back to Isidro (in Spanish): "Good news! A taxi will take you to the library!"

He stared at me, stricken. "No tengo dinero," he said. I don't have money. A posture of shame.

I touched his shoulder. "No, nosotros pagaremos. ¡No te preocupes!" We will pay, don't worry.

"¿Para mí?"

"¡Sí, capitán!" Yes, for you. I was embarassed that I hadn't explained it better to save him the confusion.

Thirty windy minutes passed. The temperature plummeted. The Beaver moon was big and bright. Isidro told me things I didn't understand in Spanish. I pretended to understand. I called United Cabs again. "It’s still in reservation phase," the lady said. "We're looking for a wheelchair vehicle. Keep waiting."

Another thirty minutes passed. I called again. "It’s still in reservation phase," she said. "Keep waiting." Another fifteen minutes passed and I called again. I was just antagonizing her now.

"Is the reservation phase going to end, can you please tell me? Will you for sure find a cab to come?" She sighed and hung up without answering.

There was no cab coming. Isidro was shivering. I thought, Could I just order the largest Lyft available and then explain? Should I empty his catheter box? I didn't have any gloves.

I opened the Lyft app and didn't see a wheelchair accessible option so I selected an XL car driven by Curry and booked the ride. His thumbnail photo was comforting. I called United Cabs one more time to cancel the reservation.

In three minutes a huge pearly white SUV with mirrored windows pulled up, soul music rippling from the speakers. I walked to the passenger window and it rolled down. White leather seats. LED track lighting. A top-of-the-line vehicle. Curry was here. How should I explain what needed to happen?

"Hi, so you can say no to this of course, but the situation is, I want to give you $120 cash to take this man to the downtown library. He’s homeless and doesn't speak English and his legs don't work and the hospital left him out here, so we'd need to lift him in and I'd need you to lift him out alone when you got there and put him back in his chair. Also he has a catheter, so. It’s okay if you don’t want to. This is a nice car, I’d understand, it's a big ask."

The driver looked at me. "What?" he asked.

"I’ll pay the trip charge either way," I said.

"Let me have a look at the situation," he said.

He got out of the car and came around to the curb. I was hit with weightless joy. It worked, the universe tuned in. This man could have built the Great Pyramids in Egypt. His bicep was bigger than my thigh. He was six feet three. A man who could lift Isidro.

"You are an answer from heaven," I said.

"Nah. But I'll help you," he said.

"Are you sure?" I said, pointing at the catheter box hanging from its cord, full enough to spill over. He nodded hello at Isidro, who nodded back, hands clasped together like he was at prayer.

"Let's go. You get one side, I got the other." He opened the passenger door, I pushed the wheelchair up against the car, then we tried to pick Isidro up. To lift and bend his body to get the top half of him in and seated before swiveling his dangling legs up and in. Isidro tried to move from his hips and pull himself along with his arms but didn't have any traction. He was perilously on the edge of the seat. It was too unsteady. We reversed course and sat him back down in the chair.

"One, two, three," Curry said, and we heaved Isidro up and onto the seat, Curry taking most of the weight, my face buried near Isidro's armpit, and at the same time realizing that the catheter tube stretched from waistband to the wheelchair arm where the box hung. "Grab the handle, man," Curry said and somehow Isidro understood and pulled himself further. We heaved him in and I held up the catheter collection box. Curry said, "Hang it up there," pointing to the coat hook above the window. I hung the pee box, praying it didn't open in the car. Curry pulled Isidro's weight into the middle of the seat, I lifted his feet inside, Curry shut the door and we smiled at each other. He gave me dap. I slid Mom's hundred dollar bill and my twenty into his hand.

I folded the wheelchair in two, pulling the seat up like a butterfly and Curry put it in the trunk.

"Do you want me to go with you?" I asked.

"Nah, I got you, baby," Curry said. "I don't know why the hospital didn't call us to transport him, we get calls from them sometimes. They shouldn't put somebody paralyzed out on the street."

"He probably didn't have Medicaid so nobody would pay them back for it so they don't even try," I said. "Thank you so much for doing this. Just text me in the app if you need more money for cleaning or something," I said.

"I'll get him where he's going," Curry said. We took a selfie.

"Take it again, there's too much streetlight," he said.

"Can I put it on the internet and tell people what a good heart you have?"

"I don't have a problem with that," he said.

Mom came up behind me and handed me four crumpled dollar bills. "Give this to Isidro." I opened the car door and put the bills in his hand, closing his fingers around them. "Adios, amigo mío."

"Godblessyou," he said again, "godblessyou." "Godblessyou," I said, and shut the door. Curry got in and they rolled off.

"That worked out," my Mom said.

"Lucky us," I replied. We walked back to the station wagon.

I fished in my bag for the nasal spray that's supposed to prevent Covid transmission and inhaled it. She handed me a little spray bottle of rubbing alcohol she uses to kill mosquitoes. I saturated my hands.

"That was fun," I said.

"It's always fun to watch you work," she said. I flushed.

"Who do you think taught me?"

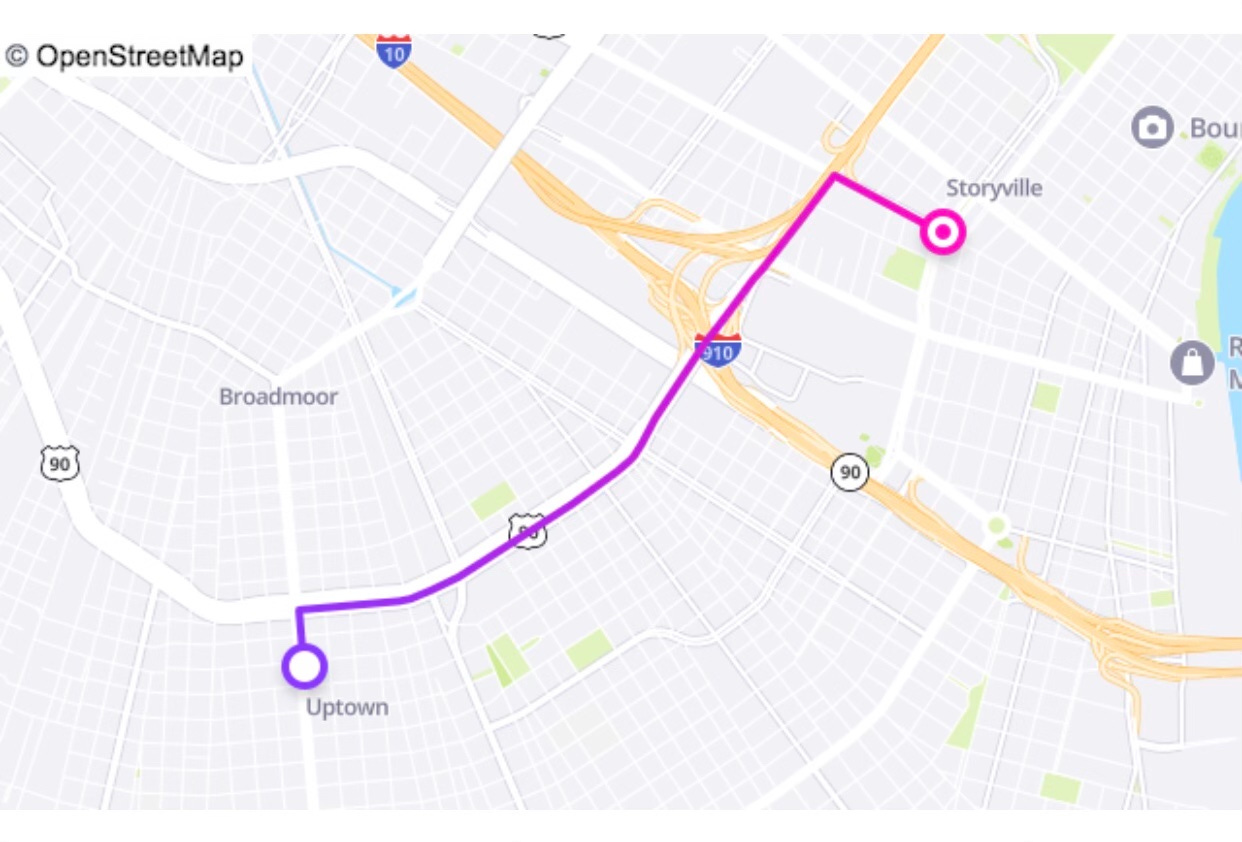

I turned on the car and handed her my phone with the Lyft app open. She selected 5 stars for the driver. We watched the little pink icon of Curry's car follow the red line on the Lyft map from the hospital to the library until the app said "Your ride is complete!"

It’s never complete, of course, and it will never be complete. But for tonight, some things were set right.

Thanks for coming along for the story.

Abriel